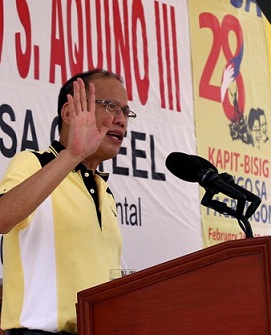

I did this article for Rogue Magazine (June 2013 issue). I’m re-printing it here as additional material in the discussion of the recently Supreme Court upheld provision on online libel in the 2012 Cybercrime Prevention Act and President Aquino’s defense of it.

In all his speaking engagements before media organizations, he has consistently grumbled about what he insists is the Philippine press’ penchant for negative stories, especially those about his government.

“It seems they have become accustomed to criticizing. It seems some are allergic to good news. When they can’t avoid such news, they look for the bad angle,” he told the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster sa Pilipinas, an association of radio and TV networks, point blank in November 2012.

A few months earlier, at the national conference of the Philippine Press Institute made up of newspaper publishers, Aquino was even harsher: He likened journalists to “crabs” who,he said, would pull down those going up.

The President’s main beef was what he deemed as media’s failure to highlight the accomplishments of his then almost two-year administration. Foreign media cared more about Philippine national interest, he took pains to stress, offering as proof a Newsweek report of the Philippines standing up to China on the conflicting territorial claims and a Time Magazine article that praised “the laggard of Asia (as) recovering the dynamism it had in the 1960s.”

Geography doesn’t matter to Aquino when he feels like bashing media.

Meeting the Filipino community on the sidelines of the Asia- Pacific Economic Cooperation in Yokohama, Japan in November 2010, he blamed media for Filipinos abroad not learning about what he said were the good things happening in the country since he became president only five months earlier.

“What is happening is that in order to get more attention, they tend to scratch on what were just tiny scrapes,” he said of Filipino journalists.

Aquino’s belief of media as an extension of his government’s information arm instead of as watchdog in a democracy is, to put it mildly, disappointing, given his progeny and the fact that he is a creation of media.

Expectations had run high that the son of democracy martyr Benigno Aquino Jr. and the late President Corazon Aquino would vigorously defend, not relentlessly attack a vibrant, albeit at times reckless, media. After all, Aquino’s father had gladly given his life in the struggle for the restoration of the country’s freedoms, including freedom of the press, a legacy his mother would eventually leave Filipinos when she ousted the dictator Marcos.And it is Aquino who owes media the publicity that helped in part catapult him to the presidency. Aquino’s record as congressman and senator was at best lackluster but largely masked by a good press he had enjoyed. It is no secret that he rode on the wave of sympathy for his mother’s death and anger over Gloria Arroyo’s widely perceived dishonest government in his journey to Malacanang.

Like majority of Filipinos, media welcomed Presidential Candidate Aquino’s “Tuwid na Daan (The Straight Path)” philosophy that promised governance reforms that he said would curb corruption and bring about the country’s prosperity. By then weary of the rising number of journalist killings, the slew of libel suits and continuous denial of access to official information during Arroyo’s nine-year rule, journalists were buoyed in particular by Aquino’s campaign pledge to support the passage of the Freedom of Information (FOI) bill that had been languishing in Congress for two decades.

Freedom of information is founded on the principle that information empowers the citizenry, and an empowered citizenry is, in turn, an effective check on governance and makes for a vibrant democracy.

The Philippine Constitution guarantees people’s right to information on matters of public “Access to official records, and to documents, and papers pertaining to official acts, transactions or decisions, as well as to government research data used as basis for policy development shall be afforded the citizen subject to such limitations as maybe provided by law,” the Bill of Rights states.

But the absence of enabling legislation has led to numerous instances of the constitutional guarantee being breached—on several occasions by Arroyo herself.

Once in Malacañang, though, President Aquino hemmed and hawed on the FOI bill. His reason, as he told one forum: “You know, having a freedom of information act sounds so good and noble but at the same time—I think you’ll notice that here in this country—there’s a tendency of getting information and not really utilizing it for the proper purposes.”

Instead, the President favors the Right of Reply bill as a quid pro quo for the FOI bill. “(In the) right of reply bill, the truth will set you free,” Aquino sought to assure journalists. “If the reporting is fair, the right of reply need not be countered.”

The President’s position betrays how uninformed he is of the workings of the press: Balanced reporting, which he has persistently harped on, is a basic element of responsible journalism that requires no legislation.

Aquino is also apparently uninformed of the danger that the proposed Right of Reply law poses to press freedom.

The bill, which seeks to fine and throw in prison journalists who fail to publish or air the other side, would in effect give politicians and nonmedia persons the right to interfere in the editorial judgment of newsrooms. A legislated right of reply would be violative of the Constitution provision that “no law shall be passed abridging the freedom of the speech, of expression or of the press.”

For lack of strong support from the President, the FOI bill failed to sail past the 15th Congress when it adjourned in February, dashing media’s high hopes.

Instead, what the media—and the public—got was a big blow from the Aquino government in September last year. The President signed the Cybercrime Act of 2012 that increased fines for computer-related libel 12 times those provided in the Revised Penal Code and doubled the maximum prison term for the offense from six to twelve years.

Media practitioners see the signing of the Cybercrime Law as adding insult to injury; they have been working to de-criminalize libel. But the President said, “I do not agree that the provision on online libel should be removed. Whatever the format is, if it is libelous, and then there should be some form of redress available to the victims.”

Thankfully, the Supreme Court has issued an indefinite temporary restraining order on the implementation of the Law.

To be fair, the environment of press freedom under the Aquino administration has improved from the previous administration when First Gentleman Mike Arroyo was filing left and right libel suits against journalists whose articles had displeased him. A number of government offices, like the Office of the Ombudsman, have lifted restrictions on access to public documents.

But press freedom is not a stand-alone attribute in a democracy. It goes hand-in-hand with strengthening other institutions like the justice system.

In November 2009, 32 media workers were killed together with 26 others when a Maguindanao warlord ambushed a convoy of his political opponent in what has been described as “the single deadliest event for journalists in history.”

Almost four years after the massacre not one of the 190 accused has been convicted, earning for the Philippines third place among countries with a “culture of impunity,” based on rankings made by a New-York based Committee for the Protection of Journalists.

Risks have not dampened the dynamism of Philippine media. Not even a whining president.