WHEN are you due? I asked a PR professional last week, two months after she gave birth. In my defense, I was seated when she approached me and I looked up at her face, not at her tummy. She said it was obvious we haven’t seen each other for some time, while, involuntarily I think, patting her tummy.

A colleague looked horrified at the faux pas. Technology, I said to explain myself, failed me. I had emailed her just a few days earlier and got a vacation auto-reply about her being on maternity leave.

Had I been on Facebook, I would have known about her giving birth. But I have been mostly off the social network and didn’t know this.

Epic fail, indeed. My phone, I thought to myself, should have given me that piece of information.

Imagine this: as you head to a meeting, your phone automagically presents you a dossier of people you are scheduled to meet with by scouring data on social networks, e-mail communications, blogs and calendar items.

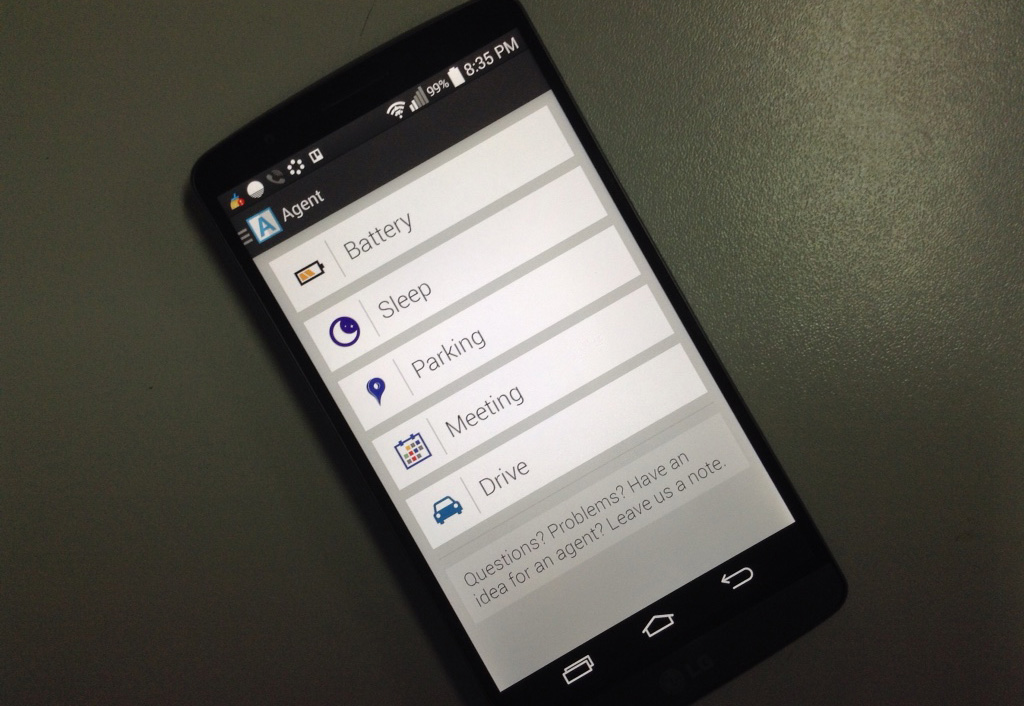

DIGITAL NANNIES. Apps like Agent for Android can serve as digital butlers or nannies. Among its other features, Agent automatically detects whether you are driving and turns your phone silent, rejects calls with a text message that you are on the road and reads out any SMS that you receive.

Or how about this: as you walk in a mall, your phone presents you with information on people, whom you do not know from Mark Zuckerberg, around you with context provided by LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter and blog updates and data.

That isn’t far out. In fact, apps and services are already available to provide a rudimentary version of a system providing you ambient information on people, places, things and events.

For location, Foursquare and later, Swarm provided us updates on where our friends are.

Apps like Rapportive provide contextual information on email correspondents. I can’t recall now for sure but one such service displayed the lovesick tweets of a reporter who emailed me her story. These were meant for her boyfriend but the service I used displayed it alongside her contact details to provide me contextual information. Too. Much. Information.

But that’s in our very near future–a future when information is widely available and delivered via mobile devices and wearables and in the context of space and time.

With developments like those, it is understandable for people to push for the “right to be forgotten.” The European Union, for example, allows people to petition for articles on themselves deleted from search engine records. Those who have been convicted of a crime and do not want this information to be widely available when people search for them can petition to have the data scrubbed from search engines in the EU.

But despite the move by the EU, technology will move such that information will become even more widely available and pervasive.

That will have profound implications on society, productivity and the way we do business. It will truly be — as the jargon de rigueur of our tech generation puts it — a disruption.

Now, if only I could assert my right for that faux pas last week to be forgotten.

The post Tech and ambient information appeared first on Leon Kilat : The Tech Experiments.