(With apologies to my editors at the STAR for uploading this a day early, for reasons made clear below—so people will know why I might be out of reach and out of circulation for a few days!)

I SAT up from my work and watched the TV more closely one day last week when I heard the news story about former First Lady Imelda R. Marcos weeping over what she claimed was her present state of penury. She was now so poor, she said, that she was having to tap into her late husband’s meager pension as a veteran, just to get by. It might have been the story of an epic downfall—if it were true. I have my own suspicions, but whether it is or not is something beyond my personal competence or interest to establish.

The image did remind me of the two instances when I met Mrs. Marcos face to face. The first was a brief encounter. It was sometime in July 1972, when killer floods were ravaging Luzon; I’d dropped out in my freshman year to work as a reporter for the Philippines Herald, and, being the eager beaver in the office, was given all kinds of odd assignments. One of them was to go to Malacañang one wet morning to check out the Palace’s relief efforts. I was led to a hall where Mrs. Marcos stood before a huge, pyramid-like mountain of “nutribuns”—enriched bread loaves—that she had amassed to send out to the famished poor. I frankly don’t remember anything of what I discussed with her afterwards. I was 18, and—while also a card-carrying anti-Marcos activist who just seven months later would find himself in martial-law prison—I was star-struck.

Our second encounter was by no means brief. Indeed, it went on and on. It must have been around 1977; I’d just begun working as a scriptwriter for Lino Brocka. One day we got a call to present ourselves at the Goldenberg Mansion, now a state guesthouse near Malacañang, to meet with the First Lady. When we got there, we realized that all the luminaries of Philippine filmmaking had been assembled for a massive film project on Philippine history, from Magellan to Marcos. Every director and his writer were assigned a historical segment to shoot; Lino and I got the Gomburza episode.

We were seated around a table flanked by floor-to-ceiling mirrors and silver, silver everywhere. For many hours, Mrs. Marcos lectured the gathered directors on her vision for the movie and on her penchant for “the true, the good, and the beautiful,” with a pronounced emphasis on the last (“No shots of slums or squatters, please!”). There was still daylight when we had stepped into the mansion; it was past one or two in the morning when we rose to leave—but not before we got a personal tour of the place, which contained some of the Madame’s collections, including a piece or two from Angkor (with a book opened to a page showing a picture of the same item). They handed us curfew passes, but I can’t recall how I got home, since I had no car and you couldn’t get a taxi past curfew time. The multimillion-peso Kasaysayan movie did get shot, in bits and pieces, but it was never shown. (It wasn’t a complete waste: in Lino’s portion was a young actor who took the part of a Guardia Civil, by the name, then unknown, of Philip Salvador. It was, if I’m not mistaken, his first break.)

I was tempted to think for a second, after witnessing Mrs. Marcos’s TV outburst, “How the mighty have fallen!” But I thought again, and moved on to the next bit of news.

IF THINGS go according to plan, I should be in semi-hibernation these next couple of weeks, following what I can only delicately describe as a surgical procedure scheduled to be performed somewhere in my nether regions—right about now, while you’re reading this newspaper. Never mind, for the time being, what that operation is. I knew this was coming—have known it for about a year—and, like a typical guy, kept putting it off until the last possible minute. I’m a boy (the minute men step into a hospital, they revert to boyhood); boys don’t like being poked, having been raised to believe that we should be doing whatever poking needs to be done. (On the other hand, women—as Beng never tires of reminding me—live with pain all their lives, and face scissors and scalpels with stoic equanimity.)

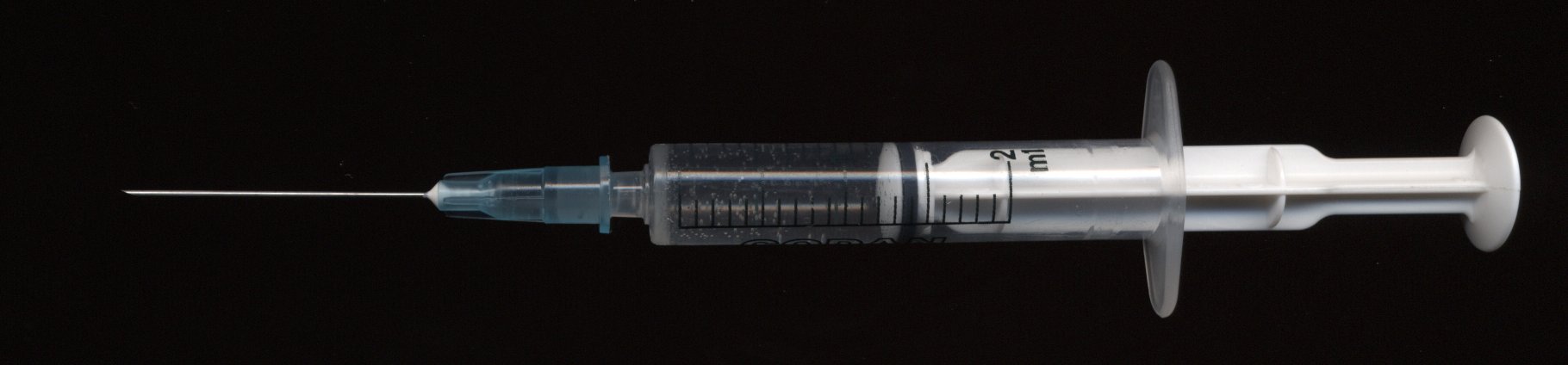

When the hospital nurse sat me down last week to draw blood for an alphabet soup of laboratory tests, I cringed, and looked away as she swabbed and palpated my arm for a big fat vein, forcing myself to think of ice cream, rare vintage pens, Angelina Jolie, and a straight flush on the flop. I hate needles; I carry with me the grade-school-clinic memory of syringes bubbling in stainless-steel tubs over tongues of purple flame. The word “inoculation” or “vaccination” was a death threat.

I should be kicking and screaming, but I find that something about hospitals soon turns my fear into resignation, and my resignation into abject docility. A nurse’s smile could be all it takes to induce me to gulp down a gallon of castor oil and waddle off to the bathroom to surrender my precious contents. I’m a pussycat in blue pajamas.

Strangely enough, I like hospital food and airplane food—the kind of moist fodder that my finicky friends would just as soon feed to their dogs. After the blood exams, I dragged Beng down to the hospital cafeteria to break my night-long fast, ordered adobo, pancit, and rice (with an operation around the corner, why worry about cholesterol and carbs?), and ate like a condemned man, making jokes that Beng didn’t appreciate about the plenitude and freshness of meat in the place.

Then we went back up for more tests, this time with a kindly but sharp-eyed cardiologist, who looked hard at the peaks and valleys of my printout before sending me back down to the Heart Station for yet more tests—in the first of which I could hear my heart on some loudspeaker going ga-thump, ga-thump, and the blood going spluuurkkk, spluuurkkk in what I suppose were the ventricles. And then they put me on a treadmill—to which they should have attached a grinder processing bushels of corn, because it seemed a complete waste of labor, otherwise—and made me run in three-minute cycles that kept getting faster and faster.

My knees were turning to spaghetti and I was thinking of passing out when I heard the cute lady doctor who was pressing the buttons say, “It would be nice if you scored higher than XX,” (I forget the exact figure) so I dug deep into my psychic reserves, played the Chariots of Fire theme in my deoxygenated brain, and finished the last cycle just like in the movies, where the champion breasts the tape in slow motion, on behalf of all balding, undersexed, overweight 55-year-olds.

Again, as you’re reading this, I should be in some kind of post-operative haze. (Last week, when I told her about my forthcoming ordeal, my colleague and former professor Amelia Lapeña-Bonifacio assured me, “If you have faith, you’ll be visited by St. Martin de Porres, who appeared before my nephew in the hospital. Do you know what he looks like? He’s black, and he carries a stick.”

I’ll be waiting, ma’am. If an orderly resembling Barack Obama comes into my room with a mop, then I’ll know that I didn’t give up all my faith with all that blood and the other day’s adobo.

(Thanks to wikimedia.org for the pic above.)